Prison Reform in Malawi: Let's Valorize Inmates' Talents

- Tiunike Online

- Jan 21, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 21, 2020

Malawians who will have been of age (or just sane) during the eighties and early nineties will recall the famous Kasungu Prison field that opened itself westwards and outwards across the M-1 road at Kasungu Turn-Off on the northern side of the municipality. Year on year, the crop was green and the thick-green colorization under budding tassels into the western horizon never disappointed for an admirable spectacle. The field was the agricultural marvel that Ngwazi Dr. Hasting Kamuzu Banda would never miss every year on his nationwide annual crop-inspection tours. It was a big deal. And although all this was the result of strict discipline, funding and some undoubted ruthlessness, the harvest ensured no prisoner went to bed hungry.

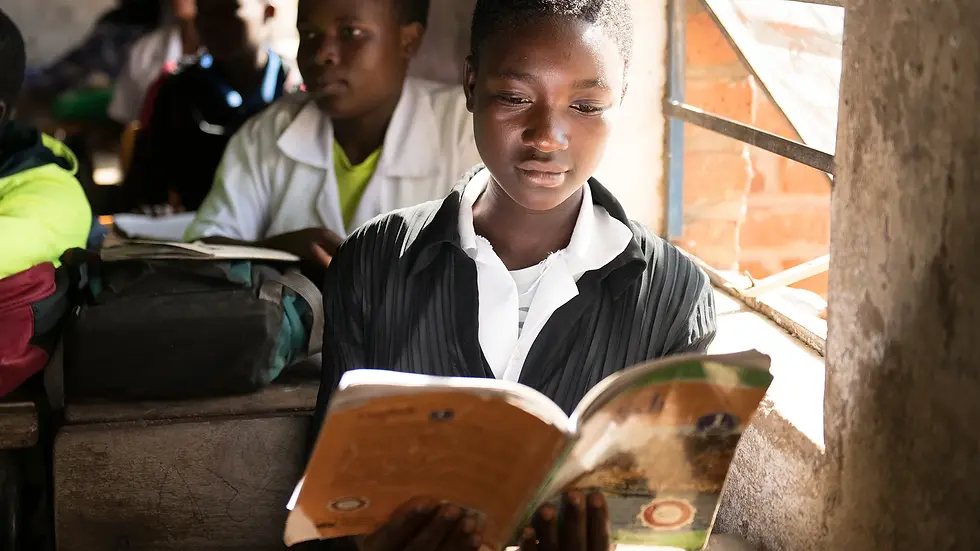

Today, Malawi’s prisons are known for something completely different. The picture of our prisons bears the imagery of overcrowding, filth, disease and hunger. A 2017 article from four researchers from UNIMA and LUANAR, published in the Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development, cites that a prisoner is entitled to a single meal a day in our prisons (full article here). The feature picture of this article (above) was part of a New York Times documentary slideshow on Malawi’s prisons that requires no words to explain the plight of inmates in the country.

Even for Malawians who’ve never been in or at a Malawian prison, the rumor that turning in bed at night in these conditions has to be orchestrated does not quite spare them. The mention of “bed” shouldn't mislead to think there are any, as Malawi’s prison beds are in fact a hard floor space encircled by cell walls. So, overcrowding means it takes rolling the body over in tune with everyone else turning. It must be unidirectional and conducted under one leader whose authority all sleeping inmates must heed.

So, although in many ways used to scare anyone from finding oneself on the wrong end of Malawian law, the picture of crowded prison cells, where sleeping has to be an art of managing minute spaces, is as vivid as it is real.

Nonetheless, the number of inmates in Malawi continues to grow.

The chart below uses statistics from the Malawi’s Ministry of Home Affairs and Internal Security and shows that between 2000 and 2017, the number of prisoners has grown from 7,728 to 14,795, a 91% increase. With slower growth in financing, prison conditions can only get worse.

There is great absence of effective interventions to expand the size of prisons to provide decent living conditions even for the current numbers of inmates. The 2017 Global Prison Trends (full report here) notes the underfunding of the country’s criminal justice and court systems is a major challenge, which we deem hampers human and financial resource availability.

According to this website, there’s a sizeable vacuum of industriousness on the part of the prison services to make the system work for the country and for the inmate. At the growing rate of incarceration, large inmate populations will continue to burden the country’s security especially as resources to contain inmates within the compound become overstretched. Already, a known fact is the worsening physical and mental health condition that pose a further strain on the economy. Moreover, our government budget seems in no hurry to cater to preventing such consequences, yet our policymakers fail to turn these institutions into self-sustaining machines that could bring about positive financial spillovers into the economy.

But what if we resourced Malawi’s prisons with programs that unleash the potential of inmates, by developing and accentuating their skills?

Such a concept espouses the viewpoint that prisons can be systems that are overpopulated not with felons but skilled workers who could produce valuable goods and services for society. We would build on the simple reality that incarceration hardly knows any eligibility criteria beyond offence of the law, and so reckon that the walls of our prisons do receive people from different educational backgrounds and talents that are still productive.

We have seen a few examples. The Zomba Prison Project (a band) made it as far as a 2016 Grammy nomination. The Kasungu Prison maize farm along M-1 makes for a delicious example. We must, instead of seeing the limitations, embrace the wide spectrum of capabilities of inmates in our prisons. We must envision that they can perform economic analyses, review national educational materials for the Ministry of Education, indeed sing, do artisanal work, fix government vehicles, farm tractors, and much more. Prisons can set up schools where inmates receive an education that is delivered by fellow inmates. Maybe some prison wardens can benefit as students too!

But the idea risks the ridicule of some human rights advocates. It may irk them on account of inmate rights, where care must be done so as not to profit on the blood and sweat of people held in confinement. Naturally, the argument that we make in this article presumes a well-functioning justice system, where one is imprisoned for a proven offense for which they must pay their debt to society. However, working is one means for society to recoup on the losses that inmates will have brought. Our argument, then, follows that working productively will not only enhance output and quality, but will fully utilize the idle skills of inmates while building the capacity of the skills and those of others.

But prisons may also lease these skills, under a transparent regime, to private sector institutions that would benefit. The condition could be that such employment is done under the promise to pay a service fee to the prison service but also enhance, where possible, the talents of the inmates.

Underlying these arguments, then, must be a solution to the human rights challenge: Pay prisoners for work. This website claims no expertise in prescribing what the best remuneration for the different skills employed in prison would be. But we are convicted that skills development and a predetermined remuneration – routinely deposited into the inmate’s bank account during the duration of their service – is feasible, tractable and is probably the best way to reintegrate once-offenders back into society with minimal risk of a repeated offence. Foreign prisoners may have some cash to return home or settle where it is safe for them.

This calls for important policy reforms. First of all, it means changing prisons from a government department into a national parastatal that is subject to the supervision of not just the Ministry of Home Affairs and Internal Security but also under the Department of Statutory Corporations at the Office of the President and Cabinet. There is an obvious need to turn Malawi’s prison services into self-sufficient institutions that should produce goods and services that are part of society. The means through which inmates deliver these goods and services may frequently allow for supervised interaction between inmates and non-offenders in the workplace.

This should be considered a good thing rather than a spectacle we frequently frown upon so that our inmates see the world into which they would return to someday.

Comments