Is A New Vision for Malawi Needed to Close the Poverty Gap?

- Tiunike Online

- Jun 1, 2020

- 5 min read

It’s 2020, and Malawi still stands at a crossroads. We are faced with an economy in tatters, a deteriorated social system that continues to honor tribal divides, a dilapidating environment, and an exceptional ability to deny our institutions the autonomy to hold our democracy together. With a Vision 2020 that was attainable, we could have now been celebrating a new era where our middle-income status would have been leading us to new heights. 2020 would’ve been the year to redefine ourselves.

Adding 7.5 million people to our population (from 10.5 million to 18 million) in the 21.5 years since 1998 has been most commendable of our achievements. Unfortunately, this has done little to lift Malawians out of poverty and has in fact worsened the state of poverty, with 51.5% of our people living under international poverty line of $1.90 per day, and about 20% of all Malawians being extremely poor. Our GDP of $7.065 billion (World Bank, 2018) means every Malawian, on average, walks home with roughly $400 a year or $1.11 every single day, wanting even in the face of the national poverty line of $1.25 a day. Much of our GDP can hardly reach every Malawian, let alone reaching them fairly, whichever way you slice the pie. Instead of living the dziko la mkaka ndi uchi mantra, the Malawi of 2020 is, more likely than not, one of the worst places on earth to be poor. Behind the bubbliness of The Warm Heart of Africa are pangs of hurt and betrayal that modern politics and residual effects of a dictatorial regime continue to spawn.

We owe much of our failures to Bakili Muluzi, chief signatory to the Vision 2020 document he championed in the late 1990s, for his unique ability to mislead millions of Malawians into believing development was going to come about on account of the public mechanism, independent of citizen responsibility towards the development they wanted to see. All his successors (Bingu wa Mutharika, Joyce Banda and Peter Mutharika) have helped to exacerbate poverty, having routinely sought political and mainly personal gain using pitiable programs, one after another, in the name of developing one of the world’s poorest nations to inconceivable levels. Today, all we can do is hold on to an unattainable dream.

This doesn’t mean that literally, every man, woman and child in the country should earn this $1.90/$1.25 in cash. It only means that the shared worth of our country, especially its return to every Malawian, should translate to a minimum of $1.90 per day in different aspects of their livelihoods. The economic system should provide for every Malawian a balanced and sustainable blend of transfers and opportunities through employment, public services like education and health, and social security like old-age pensions, to mention a few strategic levers, worth at least $693 if the country will not be considered poor. Holding in mind the biblical adage that “the poor you will always have with you, …”, it cuts across as unrealistic to expect an economy that works for every Malawian. However, to the best of its ability, we need to devise a system that will transfer wealth more fairly.

Using the summary statistics above, we run a poverty gap whether we consider the national poverty line ($0.14 per capita, per day) or the more ambitious international poverty line (in which case we need to raise $0.79 per capita, per day). So, if our selection of leaders will be based on economic factors alone, then the leader that promises a more convincing argument to increase the share of our income by this much is one that we cast our vote for on 23 June. If none of them promises this, then our vote likely amounts to nothing. But, although we know that economic wellbeing is not the panacea to all of Malawi’s woes, it epitomizes a crucial need that hits close to home every time.

It’s important to note that Malawi need not do anything different to launch itself in a post-2020 development era with anything else beyond the Vision 2020. In our current state of development, we could simply change the Vision’s date to 2040, and the document would still be perfectly relevant albeit needing some minor updates.

But if we were to change some things, …

All in all, however, we need to build national wealth, that is wealth that the man, woman or child of Khombedza (Salima) will share in the same way with the man, woman or child of Namiwawa (Blantyre). Surely, private sector growth will be a crucial precondition for much of this development, but left unregulated, it’s plagued with tendencies to redistribute wealth unfairly between workers and owners of the factors of production, between investors and government, etc. As a matter of fact, it will also not materialize without a strong national capital wealth in terms of roads, energy, water and ICTs that underpin its thrift. The same way these are needs of investors, they also happen to be the same needs that the everyday Malawian has if they are to earn an education, access a job or live a decent, dignified life. In the spirit of our article on “The Edison Effect,” infrastructure development underlines the success of many sectors, including those critical to providing the human capital necessary to facilitate private sector growth.

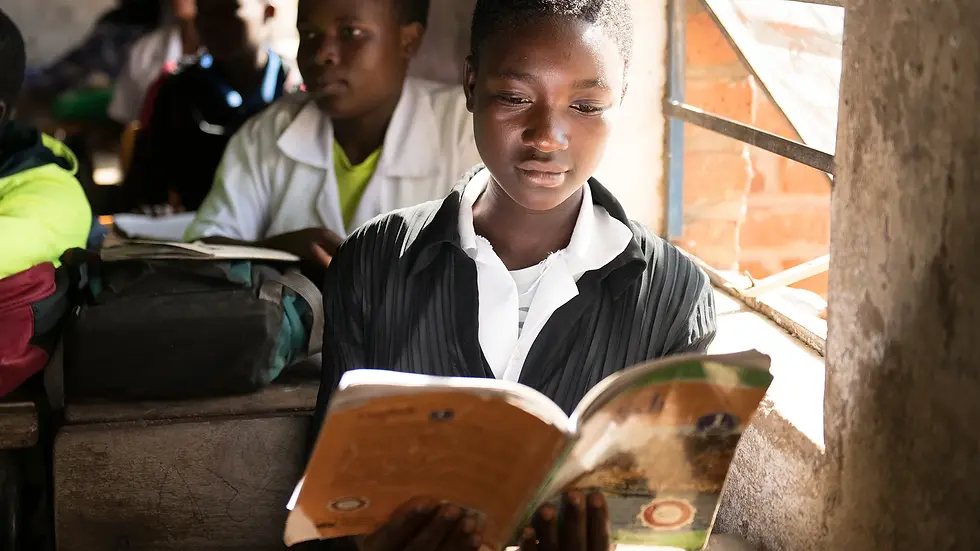

Investment in the necessary infrastructure will redistribute income and wealth if it focuses on building where it matters the most. It means investing in rural or peri-urban schools that will provide no less education than one in a bursting city, or providing the same internet speed in Ntchenachena (Rumphi) as in Area 10 (Lilongwe) so that a remote learner truly has the ability to connect to the internet when a lockdown is imposed. Everyone should have the same quality of certain basic services to be better off. There should be no need to treat non-communicable diseases like cancer and diabetes in large, urban hospitals when admission services are required for a patient in Neno. Quality infrastructure must be planted and localized in ways that do not inflict more poverty on those that must access public services.

A visionary post-2020 agenda must also recognize how Malawi’s 2018 population pyramid shows only 3% of the population is above the age of 65. A heavy investment in the aspirations of younger people is a foregone conclusion. It amazes how the age distribution of our leaders does not seem to represent this demographic, with the youngest still being senior Mr. Muluzi, who entered office at 51. Investing in the youth should mean stopping to hoodwink them into the hope of a future they will never attain; already The Nation reported massive divergence of the loan funds to ghost accounts just this April (someone will have to be held accountable someday). Our youths, instead of creating aspirations around minute Mardef loans, they must be encouraged into a culture of building things so that we can develop not only development-oriented entrepreneurs but also future employers. A youth-focused agenda will also justify embracing technology for production efficiency. Planners must, then, foresee that technology should not just enhance our pace to produce but also create jobs through it. Therefore, they should align technology jobs with requisite education that will expose young people to adaptation.

This website, cognizant that this must all be financed, advocates for progressive taxes as much as wide-based taxation systems that ensure all Malawians pay for their development. The latter is to make it fairer for all Malawians by ensuring that every able-bodied Malawian is included to encourage the responsibility senior Mr. Muluzi robbed many Malawians of.

Although the emphasis may slightly differ, nothing in this article has not already been elaborated in the Vision 2020. Our shortage, however, has been of credible institutions to deliver for its people.

Comments